Superbugs In Your Backyard

Superbugs are no laughing matter. They might be tiny, but they have the potential to undermine whatever medical progress humankind has made. Today, the superbug threat looms bigger than ever, an insidious pandemic happening right under our noses. And as such, we should be scrambling to contain this emerging threat, especially in Southeast Asia. In this article, I talk about how we’re perpetuating this silent pandemic right in our backyards in the region.

Superbugs: a quick crashcourse

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is an ongoing silent epidemic across the world, which many countries have limited capacity to detect.

– Kakkar et al (2017), in Developing a situation analysis tool to assess containment of antimicrobial resistance in South East Asia

Superbugs are micro-organisms such as bacteria, viruses and fungi that are stronger than usual. They are “super”-bugs because they have the ability to resist certain medication that were designed to inhibit their growth or kill them. Yes- this means that the medicine we developed to treat diseases they cause can become useless.

This resistance is also known as antimicrobial resistance (AMR). Just like how our immune systems become stronger after fighting off infections, micro-organisms can evolve to become stronger after being exposed to antimicrobials such as antibiotics.

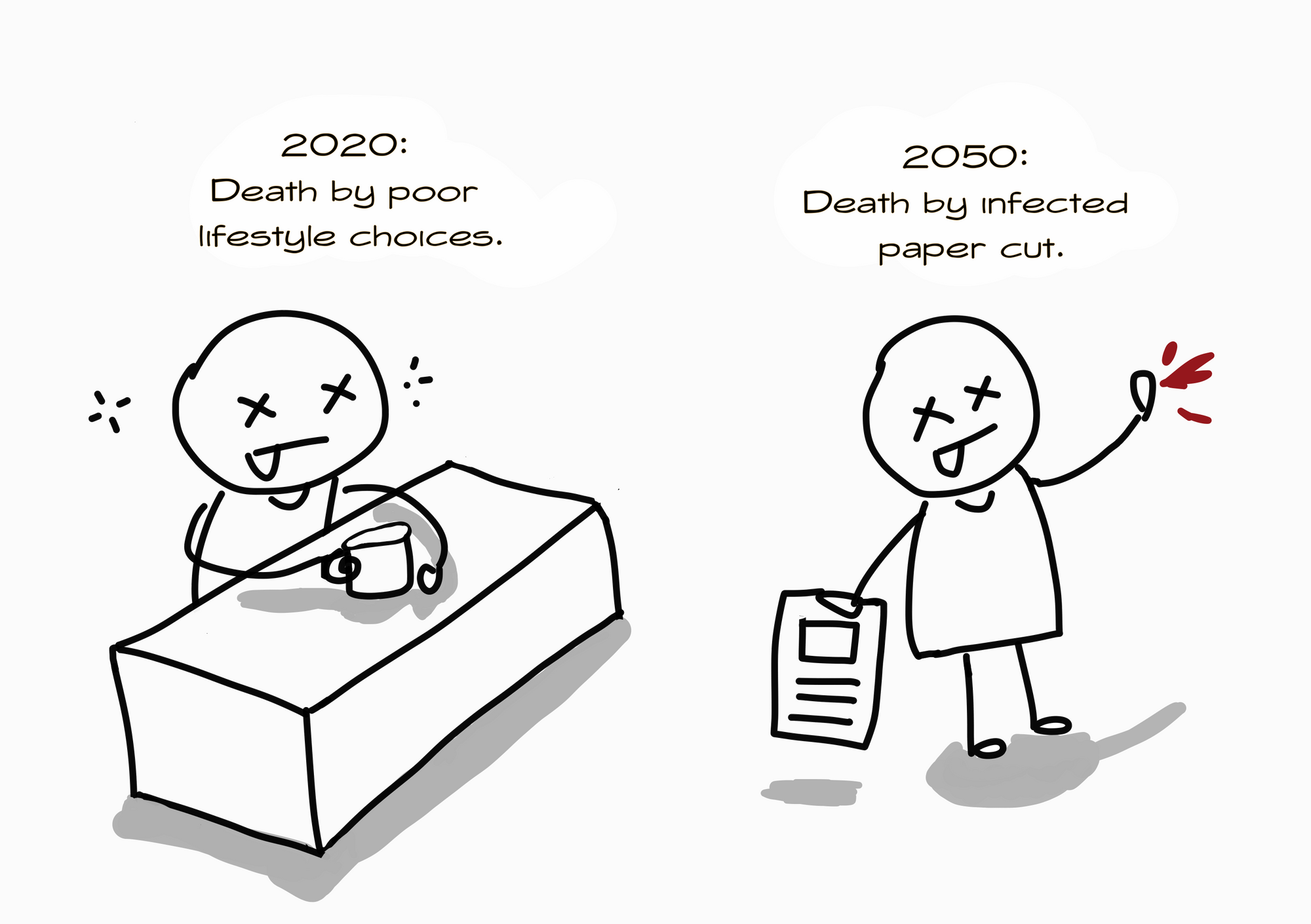

The problem is, AMR has become a major threat to global health security today. If we don’t do more to fight it, we might enter what is called a post-antibiotic era by 2050: a world where antibiotics are rendered useless (antibiotics are just one type of antimicrobial agent. We’re not even talking about anti-parasitics and anti-virals yet). This means that even something like a simple cut can cause a fatal infection. If a minor injury can threaten the life of a healthy individual, what’s there to say about complicated surgeries and chemotherapy that require antibiotics to prevent infection? Further, these complex procedures are often done on people who are already ill.

AMR is driven by many factors, but this article will focus on AMR in the environment. In particular, I will talk about AMR in the environment in Southeast Asia. Why? Because here, the problem is serious- and I mean serious. And trust me, you’ll find yourself caring because no matter which part of the world you’re from, what happens in this region will affect you.

1. Antibiotics are being dumped into our rivers everyday.

Global pharmaceutical manufacturers have relocated their operations to Asia to remain competitive. India and Bangladesh are currently the powerhouses of pharmaceutical manufacturing in Southeast Asia. While their status as emerging pharmaceutical manufacturing countries (EPMCs)4 has been a boon for their economies, it is feeding an insidious AMR catastrophe.

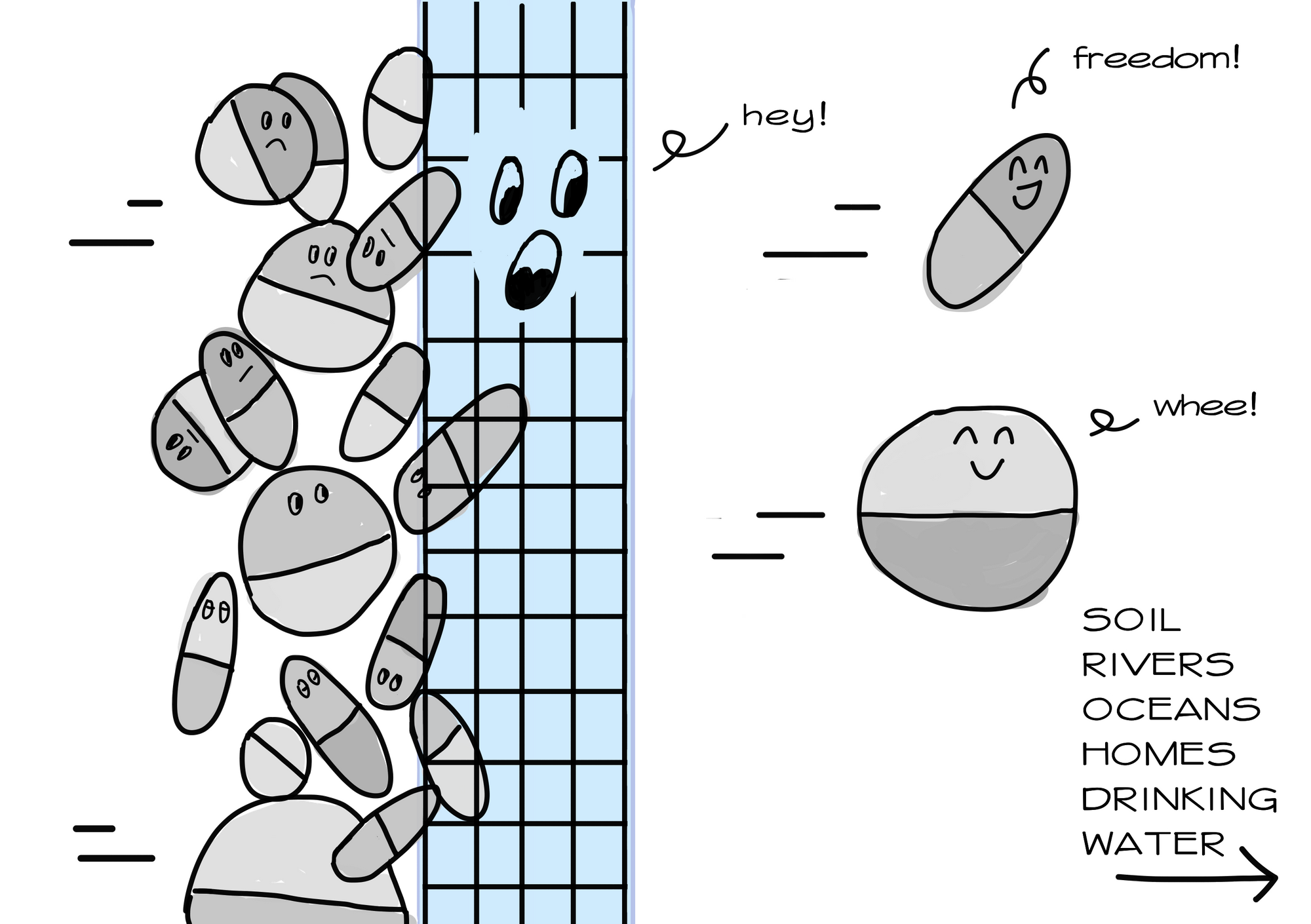

Just picture this: pharmaceutical plants based in India and Bangladesh alone release up to several kilograms of antibiotics through wastewater into the environment daily. This amounts to tonnes per year! Just imagine the sheer amount of bacteria exposed to antibiotics in rivers, oceans and the soil every day.

And that’s just from a sample of industrial discharge alone. Majority of antibiotics are consumed by humans and animals. Did you know that half of the antibiotics we consume are excreted in our faeces in their active forms? We release these antibiotics and their residues into the environment via hospital and community wastewater!

2. Superbugs are entering the food chain.

When antibiotics and antibiotic residues from wastewater enter our lakes, rivers and oceans, they don’t just disappear. They accumulate. They enter our food chain. Our plants are not spared either. Like in animals, antibiotics can bioaccumulate in leaves, stems and roots. As a result, resistance emerges, with antibiotic-resistant bacteria going on to share their resistant genes with other bacteria, and the cycle continues up the food chain. Soon, both the antibiotic residues and the resistant bacteria can end up on our dining tables.

If you’re from a high-income country, your government has likley enforced strict regulations on the permissible levels of such residues found in food products. However, such domestic regulations don’t exist in many Southeast Asian countries. Given the high levels of antibiotic use in agriculture and aquaculture, in addition to the dumping of antibiotic residues in the environment, the locals are most probably unknowingly consuming antibiotics and resistant-bacteria from their food and drinking water. Also, given the ubiquity of air travel, resistant bacteria can easily be transmitted across national borders.

3. Antibiotics are notoriously tough to remove from wastewater.

Surely, there must be technology available to remove antibiotics from wastewater? Well, unfortunately, even treated water from high-income countries contain traces of antibiotics. Our current technology is still unable to completely eliminate antibiotics from wastewater. Even advanced water treatment methods that deploy chlorination and UV radiation, which has been said to enhance elimination efficiency up to 50-90%, failed to remove selected antibiotics such as roxithromycin, sulfamethazine, and sulfamethoxazole. Inadequate technological advancement remains a problem because bacteria can still develop resistance even under low antibiotic concentrations,

It is true that some treatment is better than no treatment. But the problem is much more dire in Southeast Asia, where up to 80% of wastewater is released into the environment without treatment. And we are talking about wastewater from pharmaceutical manufacturers, hospitals, farms, sewage facilities- all of which amount to tonnes of antibiotics released every year.

Oh no, is there anything being done to stop this?

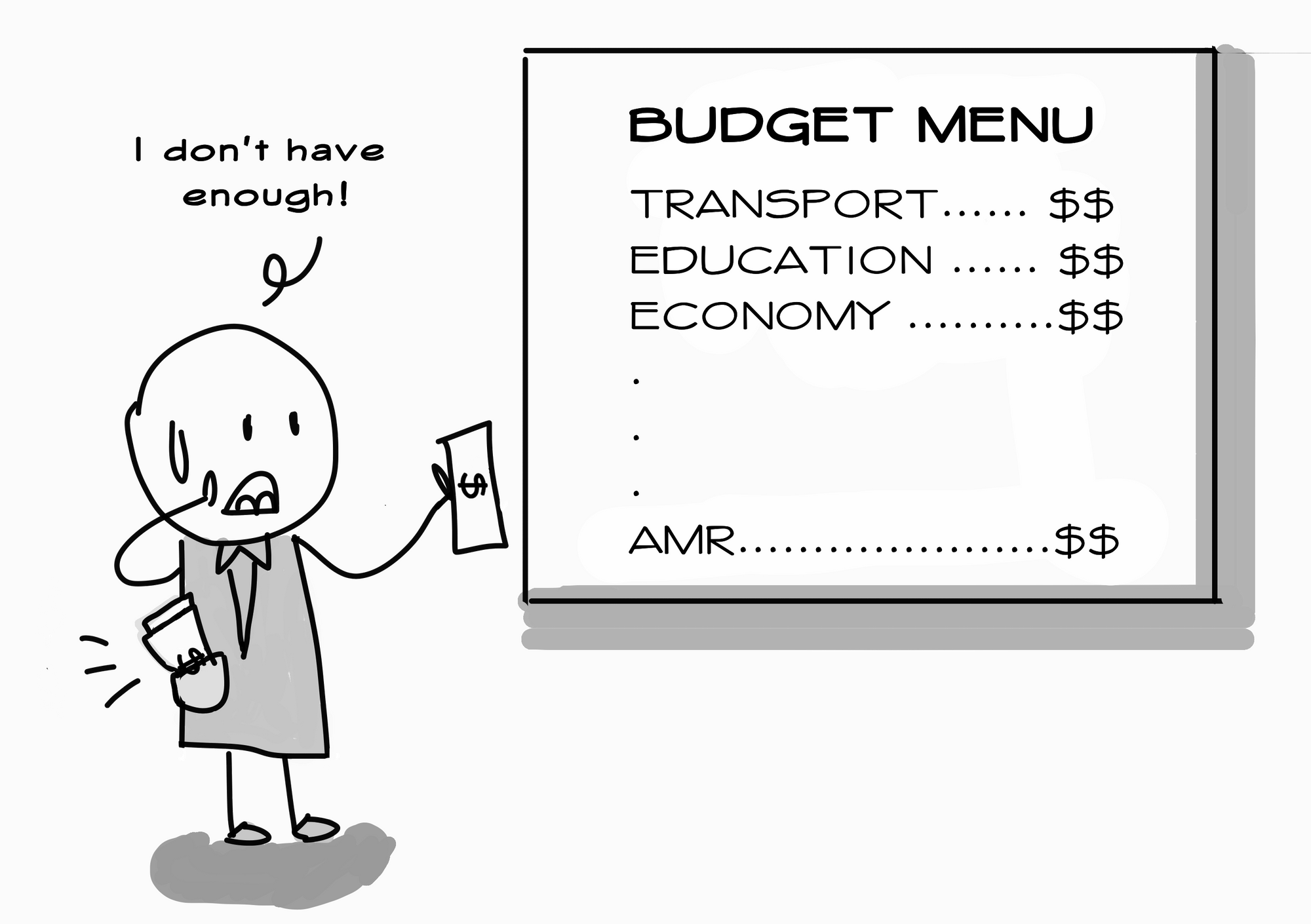

Current estimates point towards tonnes of antibiotics and their residues being released in the region every year. However, we don’t have sufficient data on antibiotic residue levels in wastewater discharge across the region, let alone a profile of resistant bacteria in the environment. Unfortunately, this is because maintaining monitoring and surveillance efforts in the environment is expensive. Think of the water, soil, crop and animal samples you have to collect!

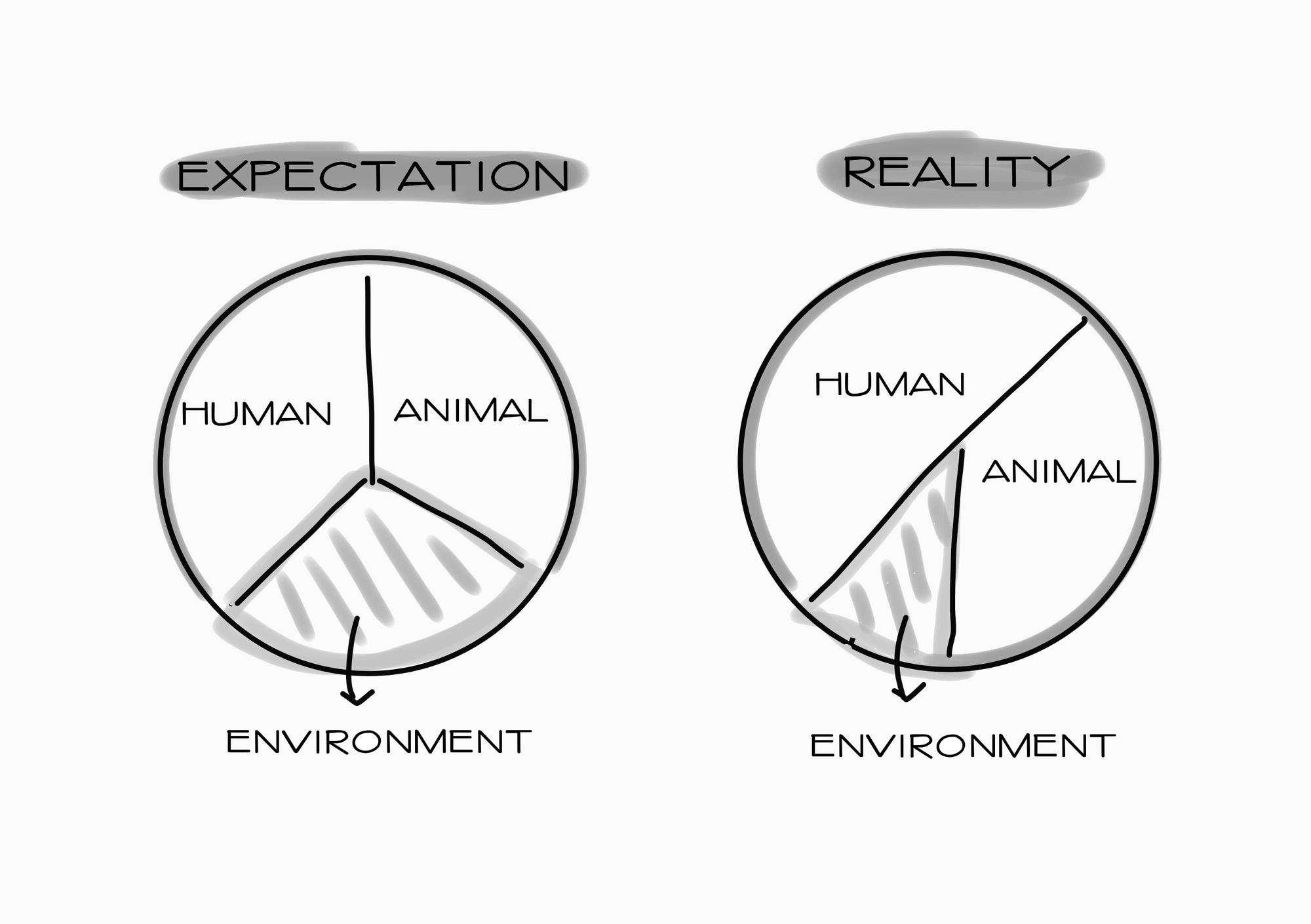

When it comes to fighting AMR, the environmental sector is, unfortunately, usually neglected. The oversight persists even though the AMR problem has long been touted to require a One Health approach. That explains why monitoring is so expensive: there just aren’t enough resources pumped in to make the process cheap and efficient.

On the bright side, there appears to be increasing awareness of this problem. Scientists are establishing thresholds for the maximum concentrations on antibiotic residues allowed in the environment.5 These concentrations will provide a benchmark for monitoring programmes to abide by. While the development of guidelines might seem insignificant, remember we only started to glean about the scale of the problem in recent years.

We have another reason to be optimistic: The World Health Organization, South-East Asia Regional Office (WHO SEARO) has been channelling more resources to understand the problem at the local level. In my opinion, simply mapping all available knowledge on the issue is woefully inadequate in the grand scheme of things, but it’s a start.

Thankfully, WHO SEARO is also doing the next most important thing: spreading much-needed awareness about the issue among key stakeholders. That means the irresponsible pharmaceutical manufacturers, health professionals, policymakers and the public will soon be learning about the scale of the problem.

What remains to be done? What can you do?

For one, there are still lots of things we don’t know. For instance, we only have estimates on the level of antibiotic residues found in wastewater from industry, farms, hospital or community sources. To take concrete action, we need proper data from surveillance and monitoring initiatives.

Second, the region’s capacity to solve the problem is limited by its resources. We need cheap, innovative technology that can help us detect, measure and remove antibiotic residues as well as antibiotic-resistant bacteria in wastewater.6 AMR surveillance and monitoring efforts among humans and animals have vastly outpaced that of the environment. We can’t run away from the need for affordable and effective technology to fill in gap in the data. Otherwise, we’re as good as fighting blind.

Lastly, we need those in power to start taking AMR in the environment seriously. When it comes to fighting AMR, all three sectors under the One Health approach must work in tandem. As such, we need stronger regulations to stop irresponsible dumping of pharmaceutical waste. We need to inject funds into research and innovation. We need political commitment to enforce the rules that have been written.

We need to slow this silent epidemic before it’s too late.

How is progress on AMR affected by COVID-19? 7

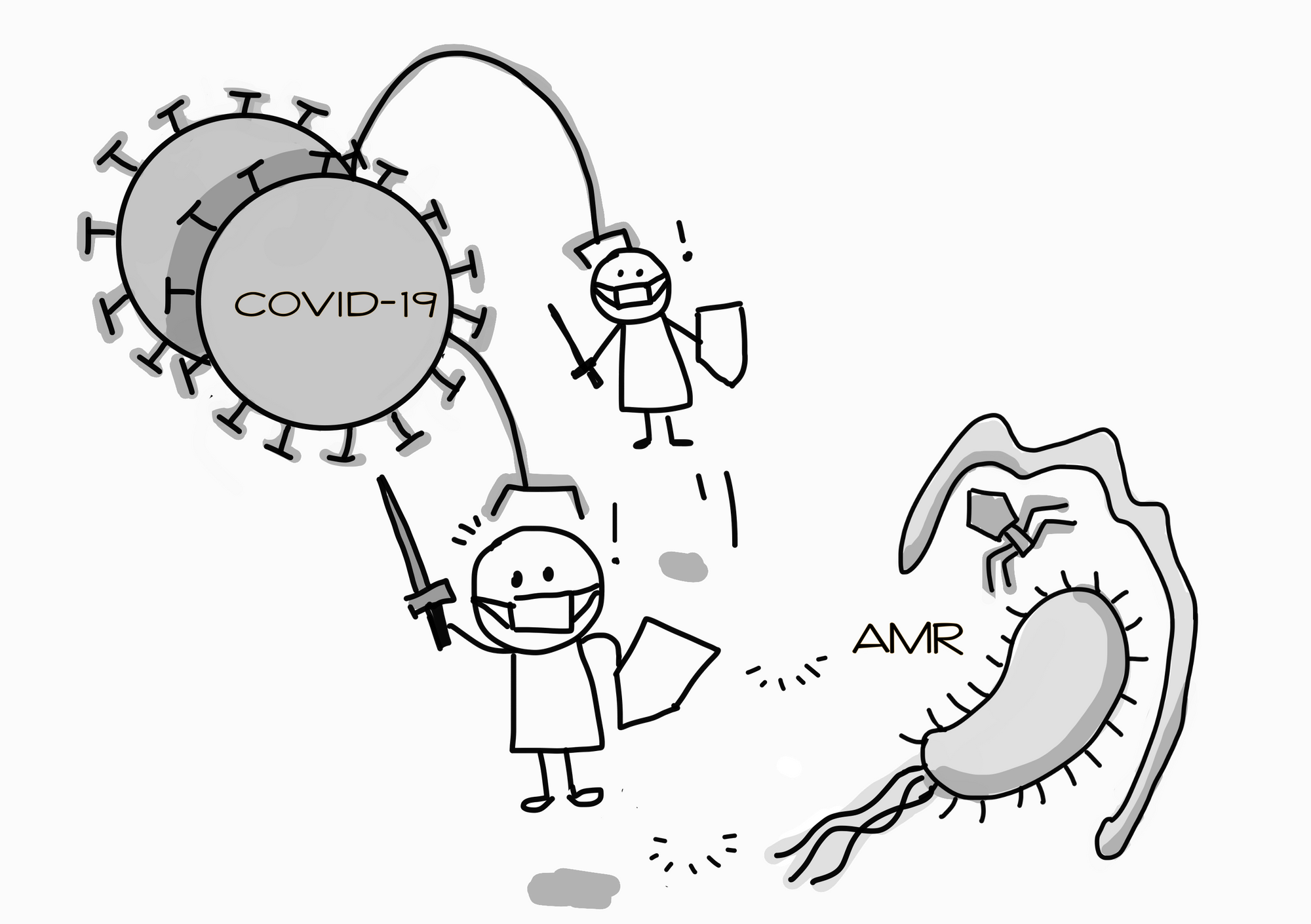

COVID-19 is the best example of a problem that requires a One Health approach. For one, the animal-human connection is glaringly obvious: based on the current literature, the coronavirus had most probably been transmitted from an animal source to humans. Second, the human-environment connection has also become obvious. Hygiene and sanitation has become top priority, both at work and at home. Countries also look to testing for virus residues from wastewater to detect community clusters.

What’s COVID-19’s relevance to AMR? I can think of two. First, the world has deployed an all-hands-on-deck approach to contain the virus. When countries mobilise all healthcare resources to fight the global pandemic, it means that resources for AMR (as well as other public health issues) are re-directed to the pandemic-fighting frontlines. Second, the current obsession with infection prevention and control has seen copious amounts of sanitiser/disinfectant use. As antimicrobials, these liquids perpetuate resistance. As we are trying to kill the virus, we are also breeding bacterial and fungal resistance.

As experts foresee the COVID-19 battle to last well into the next two years, they are calling for studies to assess the pandemic’s impact on AMR. That way, the proper mitigation strategies can be taken, so we do not compromise our response to one threat in favour of another.

Sources:

Risk assessment for antibiotic resistance in South East Asia (Chereau et al, 2017) ↩

Global risk of pharmaceutical contamination from highly populated developing countries (Rehman et al, 2015) ↩

Bangladesh, China, India and Pakistan are known as emerging pharmaceutical manufacturing countries (EPMCs).

India is responsible for 20% of the world’s generic drugs, China, more than 60% of active ingredients (which includes antibiotics). ↩

These concentrations are formally called ‘predicted no effect environmental concentrations’ or PNECs. These are concentrations of antibiotics postulated to prevent selection for resistance.

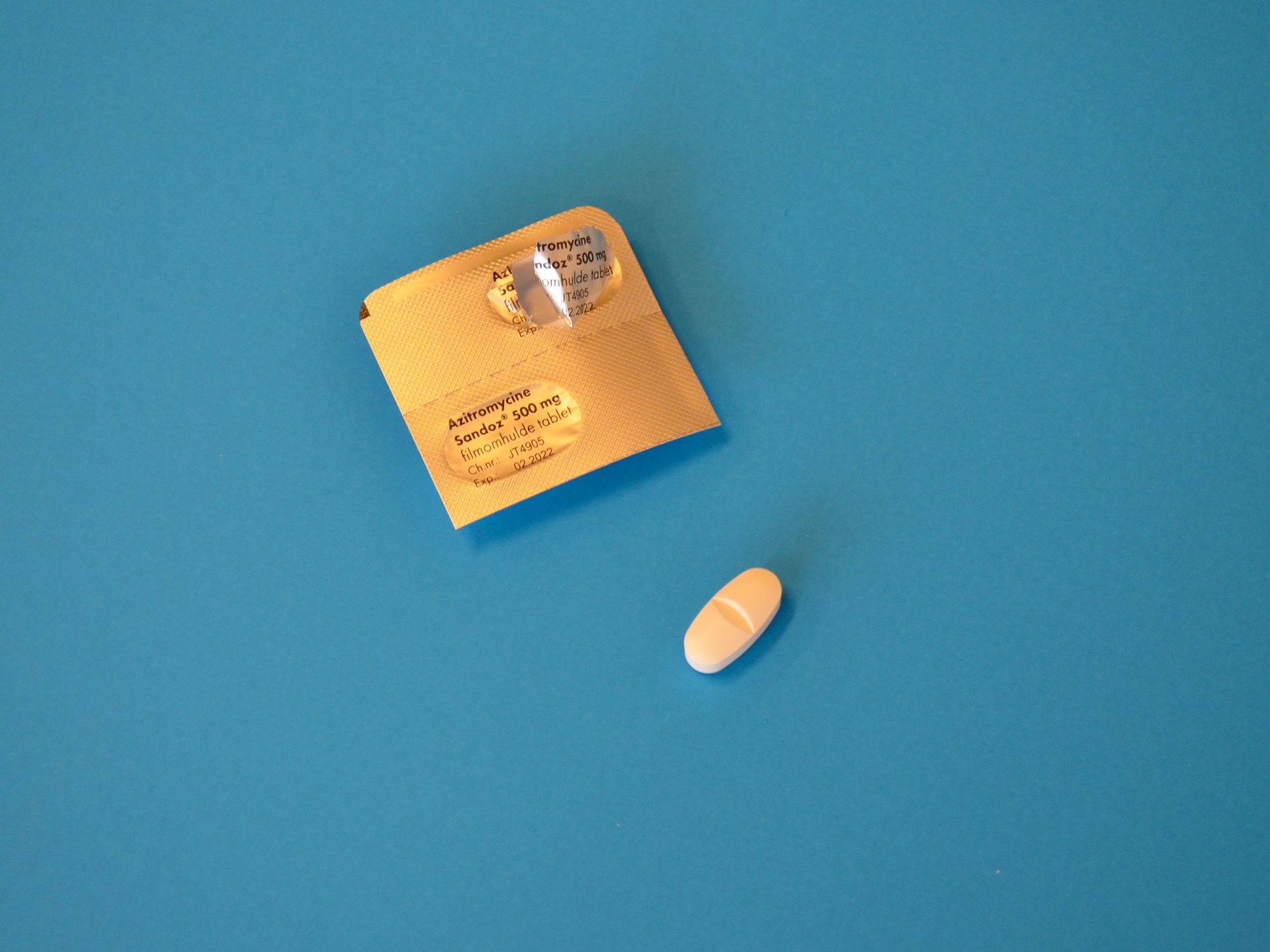

Currently, guidelines currently exist for several antibiotics such as ciprofloxacin, azithromycin, sulfamethoxazole. ↩

Decentralised, on-site treatment plants equipped to neutralise antibiotics and resistant bacteria (OSTP- Zero ARB) are possible solutions in low-resource settings. ↩

COVID-19 and the potential long-term impact on antimicrobial resistance (Rawson et al, 2020) ↩

Stay updated on the best insights from public health professionals.