Journeying into Global Health with Nikki K

This article is part of the Public Health People series where I meet with different public health professionals from all around the globe. Join me in exploring the greatest insights from their fields, their passion projects and their principles for both work and life!

Today we meet Nikki Kitikiti, better known as Nikki Kay or @afromedwoman on Twitter.

- Nikki is a public health physician.

- With roots in South Africa and Zimbabwe, she has also lived in the US, UK, Iran and has been based in Singapore for the past ten years.

- After graduating from Duke-NUS medical school, she served her residency rotations in a variety of healthcare settings.

- These settings included hospitals, primary care clinics, health policy think tanks and government statutory boards.

- With a focus on health policy and healthcare management, she has experience in strategic planning and programme management as well as health systems and policy research.

I first got to know Nikki through Twitter. An ardent advocate of resolving health inequities through structural reform, Nikki believes in patient advocacy and representing marginalised voices in policy. Despite her busy schedule, she was kind enough to grant me two hours of her time, where we chatted about her life and work over a cup of tea (keeping social distancing in mind).

While I could not help but be drawn to her amicable personality, there was also a tenacity that burned beneath her easy-going veneer. And throughout our exchange, I saw the same fiery passion for her work on Twitter come to life in front of me.

We talked about her journey from anthropology into medicine, what sparked her passion for patient advocacy and how resolving health inequities lies at the heart of what she does. I hope you enjoy this article as much as I enjoyed her company. Please, grab a warm cup of coffee or tea as you read along.

Going from Anthropology to Medicine

When Nikki graduated from Macalester College with a double major in Anthropology and Chemistry in 2008, she wanted to become a medical anthropologist.

When I asked her why she decided to pursue medicine in the end, she clarified up front: “I’ve met many inspiring doctors as a patient and caregiver but I also met and worked with some egotistical doctors who taught me what kind of doctor I did not want to ever be.” Medicine’s main draw for Nikki was the empowerment it promised. It’s difficult, she explains, for someone who isn’t medically trained to have a say in a multidisciplinary team. “It’s always the doctor in charge, even if they don’t know what’s best for the patient or the community.”

Her heart’s yearning combined with the offer of a full tuition scholarship made medicine an easy choice for her.

HIV: Her induction into public health

Nikki traces her life’s work in public health back to one thing: her personal experiences of the HIV epidemic that started during her childhood years. Raised in South Africa and Zimbabwe, she was no stranger to the devastation the HIV epidemic had wrought upon her community since the 1980s.

“It really ravaged my family. I saw my family- my aunts and uncles, dying,” she shook her head grimly. “There was a funeral every day.” Back then, treatment hadn’t existed yet. “People around me were dying of AIDS. Many children were made orphans and had to be raised by grandparents.”

More poignantly, Nikki recounts the heavy cloak of stigma that surrounded a HIV diagnosis. “And it was so heavily stigmatised. We couldn’t even say they died due to AIDS because it was so taboo. We had to say they died due to witchcraft or cancer.”

Nikki says that the most important thing is to start talking about what’s taboo. And for HIV, that meant talking about the disease, condom use, getting tested and receiving treatment. “I wanted to fight the stigma. People shouldn’t feel ashamed of their condition. That’s why I really wanted to be in the community,” she explains. While Nikki has taken it upon herself to shift the narrative as an advocate, she says that it’s not enough. “We need patient voices represented, and from the patients themselves,” she affirms.

The sobering truth about patient-centred care

What does it mean to have patient voices represented? Having being involved in both clinical work and health policy, I asked Nikki about some of her biggest takeaways.

The answer came easily to her. “In the last few years,” she starts, “ I’ve come to realise that patient-centric care is a lie.” I was a little stunned by her blatant honesty. I didn’t expect that, noting the increasing discourse around patient-centric care. Nikki shook her head. drawing from her experience during her clinical and policy rotations, she explains, “whenever we’re providing care, we don’t meaningfully engage the patient. We’re actually coming into the patient’s situation with our own biases, our own world views,” She frowns, “Medicine is a lot about experts telling non-experts what to do.”

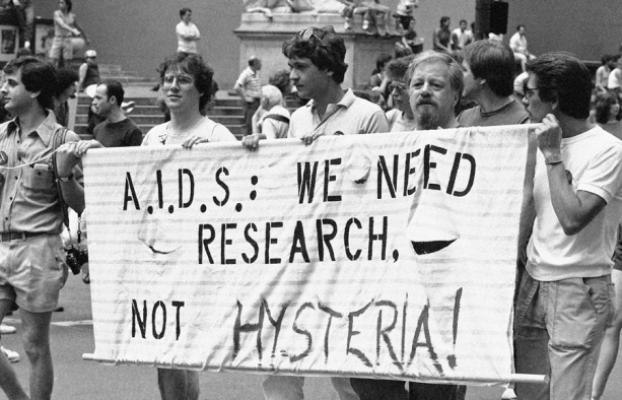

What happens when the experts don’t know better? Nikki claims that actually, many positive shifts in global health had been galvanised by patients themselves- not policy-makers or healthcare staff. What had put research for HIV treatment on the global health agenda? Who lobbied for treatment to be made affordable? It was the HIV patients and their partners and their families themselves.

They were the ones who made treatment possible. They were the ones who made treatment affordable in low and middle-income countries (LMICs). They were the ones who knew what was best for them. She cites the HIV epidemic that struck the US in the 1980s, and the same epidemic she lived through back in South Africa and Zimbabwe. “It was all HIV activists aggressively fighting for their voices to be heard, for their needs to be met.”

It was here that I started to see how patient-centred care and health inequities were intricately connected. To Nikki, the problem of unequal access to health boils down to broken representation systems. “Imagine if those voices were represented to begin with. Then they wouldn’t have to yell so loudly for those in power to hear them.”

She draws the parallel back to patient care. “We don’t have a system where the patient is given a platform to speak.” When it comes to giving those who know best a voice, she says that we still have a long way to go. “Asking them for feedback is not enough! They’re receiving the care but they’re not in the rooms where the decisions are being made.”

Nikki’s centre

Nikki’s personal experience with HIV had illuminated for her a calling in global health. Working with marginalised communities is something she that not only grounds her, but also rejuvenates her.

Back in 2011, Nikki grappled with intense burn-out during her second year at medical school. In response, she took a year off school to pursue her MSc in Global Health at the university of Oxford. As part of her thesis, she assumed the role of a research assistant with Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) and Wellcome Trust in Kilifi, Kenya.

In Kenya, she spent her time conducting participant observation research alongside a HIV vaccine trial that had been conducted among the men who have sex with men (MSM) population. At the end of her Masters, she decided to stay for another year. The two years had rejuvenated her. She said, “And when I came back, I knew exactly what I wanted to do.” She was going to become a public health doctor.

She continues to serve marginalised communities in Singapore. Nikki is a regular volunteer with HealthServe1, a Singaporean non-profit that provides healthcare, counselling, casework and social assistance to disadvantaged migrant workers in Singapore.

Health systems are meant to protect, not punish.

In the clinical setting, it can become easy for medicine to be solely focused on the individual. “What I love about public health is that a person is seen as living within a particular social and political context.”

She recalls her time spent at the Health Promotion Board, where they looked at policies that shape the environment to make living healthy easy and intuitive. “You know, if a family is poor and the parents work two jobs, it’s just going to be difficult to make healthier choices.”

Blaming one’s poor health on irresponsible lifestyle choices is as myopic as it is disempowering. In shifting the blame to the individual, you dismiss larger institutions that constrain and persecute.

If left unexamined, treating public health issues as crimes can punish the most vulnerable instead of healing them. In the US, the closure of asylums in the 1990s to early 2000s had left a gaping hole in the country’s mental health systems. What ended up filling this gap? The answer: prisons.

“Prisons have become the new asylums,” Nikki deadpanned. Reality paints a stark picture, because “once again, it’s usually the marginalised who suffer the most.” Indeed, the poor with severe mental illnesses are often systematically denied health services.

Facing severe difficulties integrating into the community, many end up turning to crime or drugs. “In the US and many other countries, we treat addiction as a crime! Just imagine if we sent someone to jail because they have diabetes- because they ‘made the wrong ‘lifestyle choices’. You want a system that protects you, not one that punishes you.” Shaping this system, is what public health is all about.

A life-changing medical patient conference

I asked Nikki whether she’s got any passion projects going on. She says that her current posting is related to her current interests. When asked to elaborate, she says that she has been inspired by patient advocacy groups, “they’re so passionate, it just rubs off on you”.

The very first patient advocacy conference she attended was for patients with rare diseases. It was a transformative experience for her. Gesturing excitedly with her hands, Nikki recalls the conference with utmost clarity. “It’s nothing like a medical conference. Here, everyone there starts off with a story.” She describes the solidarity, the humanness and authenticity that course through the beat of the event. “And before you know it, everyone in the room is hugging each other and crying.”

She bemoans the sterility of medical conferences. Even if patients were represented at medical conferences, there is little room for them to be authentic and truly themselves. This is because “being yourself is not professional.”

Once again, she raises the disconnect between the medical profession and the patient’s lived experiences. “In medicine and public health, I get that we do need to collect the statistics and numbers. But what is the lived experience? We tend to forget a very important voice in the room.”

Baby steps to patient representation

Her interests in patient advocacy has led her to her current posting at Duke-NUS. Here, she is working on empowering the patient in the healthcare setting. When I asked her how that looks like, Nikki describes her work as akin to teaching patients the ABCs of navigating the health system.

She doesn’t completely agree with the approach, arguing (in a completely Nikki-like fashion) that “it should be us that’s learning from them.” Still, she concedes that our current health systems are not structured to facilitate that. “Unlike places like Europe, we don’t have anything set up here in Asia”. Yet.

Avoiding burnout in Global Health

I asked Nikki if she had any advice for people interested in the field. And she does. If you’re interested in global health, Nikki implores you to:

- Be a team player. Global health is a multidisciplinary field. You’ll need to work with economists, sociologists, doctors and the like. You’re not going to do well if you’re “an ego-centric person”!

- Be adaptable. You’ll need to be flexible in your thinking so you can adjust to changing contexts. She suggests avoiding sticking to old, rigid ways of looking at things.

- Be a systems thinker. So you know how to investigate and identify the origins of the issues you’re dealing with. That includes having the ability to take a step back and look at the bigger picture.

- Be a good listener. Period.

- Learn to celebrate small victories. It is easy to burn out in global health because you are fighting systems of oppression that can be more than centuries old.

Above all, she stresses the need to be hopeful. It is with the very same hope that we can strive to push global health forwards.

Nikki’s favourite books on global health, patient advocacy and health inequity

If you’d like to learn more about what inspires Nikki, here are some of her favourite reads:

- AIDS & Accusation by Paul Farmer

- The Patient Revolution by David Gilbert

- The Immortal Life of Henriette Lacks by Rebecca Skloot

- The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down by Anne Fadiman

Thank you so much for reading <3 I hope you enjoyed the article as much as I enjoyed Nikki’s company 🙂

Stay updated on the best insights from public health professionals.