Forget Doctors Without Borders: On Health Systems and Capacity Building with Dr. Natarajan Rajaraman

I speak with the executive director of NGO Maluk Timor on why we need engineers, accountants, and administrators without borders instead.

This article is part of the Public Health People series where I meet with different public health professionals from all around the globe. Join me in exploring the greatest insights from their fields, their passion projects and their principles for both work and life.

Why Did I Want To Speak With Dr Raj?

We've met educators who have changed the trajectory of our lives.

I once dreamed of becoming a humanitarian worker with Doctors without Borders for the longest time. I had it all planned out: Since I had no interest in becoming a doctor, I'd either become a pharmacist or an epidemiologist, then join the MSF team and do lots of good.

It was a 2-hour guest lecture by Dr Natarajan Rajaraman (Raj) back in early 2019 that made me seriously reevaluate my conviction to join a humanitarian organisation as a healthcare worker.

Even back then, he’d struck me as eloquent-- a powerful communicator who easily outshone other professors. In his lecture on 'Capacity Building', he shared his experience in health systems strengthening projects in Sierra Leone, saying:

"We don't just need Doctors Without Borders. We need Secretaries Without Borders and Engineers Without Borders."

This quote has been permanently seared in my head ever since. It readily resurfaces in my later seminars on human rights, humanitarian aid, and international law. Time and time again, my classes reinforce the pertinence of this one quote. Thanks to Dr Raj, I realised that overcoming the nuanced challenge of inequitable access to care isn't the noble task of healthcare workers alone.

It was not until Nicola suggested that I speak with Dr Raj that I recalled this specific lecture. Recalling his powerful insights, I did not hesitate to drop him an email.

Raj is currently the executive director of Maluk Timor, an Australian and Timorese NGO focused on enhancing primary healthcare in Timor-Leste. Prior to joining Maluk Timor, Raj was head of medical services at HealthServe, an NGO that provides medical care, counselling and social assistance services to disadvantaged migrant workers in Singapore.

Raj has a background in medicine, global public health and education. Evident from his current appointments, he feels deeply for the health of vulnerable populations and post-conflict health systems strengthening. And he does that best by training healthcare workers and improving the quality of healthcare facilities.

One of my favourite things from our conversation was how readily—almost instinctively—he contextualises his responses to distinct circumstances in his life. Facts, to him, are nothing without context, an understanding indicative of his years spent in cross-cultural settings, where a prize is often placed on understanding the other side.

Raj also has a quiet way of making people around him feel comfortable. He exudes a calm presence, speaking with an incisiveness which he punctuates with good-natured humour. A bio he offered at one of his speaking events wrote: "Raj enjoys reading and movies. Raj loves cats. And motorcycles. But not cats on motorcycles."

As someone who had once been interested in joining the field, I wanted to find out: what are some key insights I should know before deciding whether global health is for me? What should I know if I want to thrive in this field?

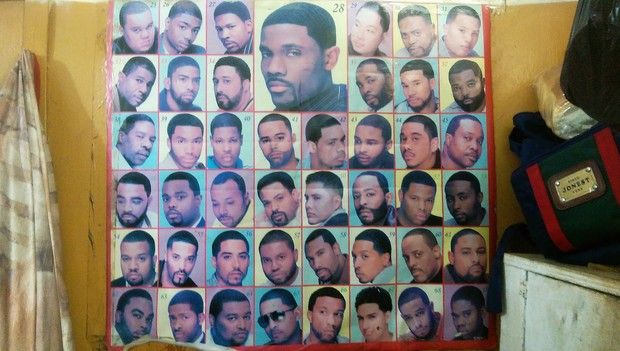

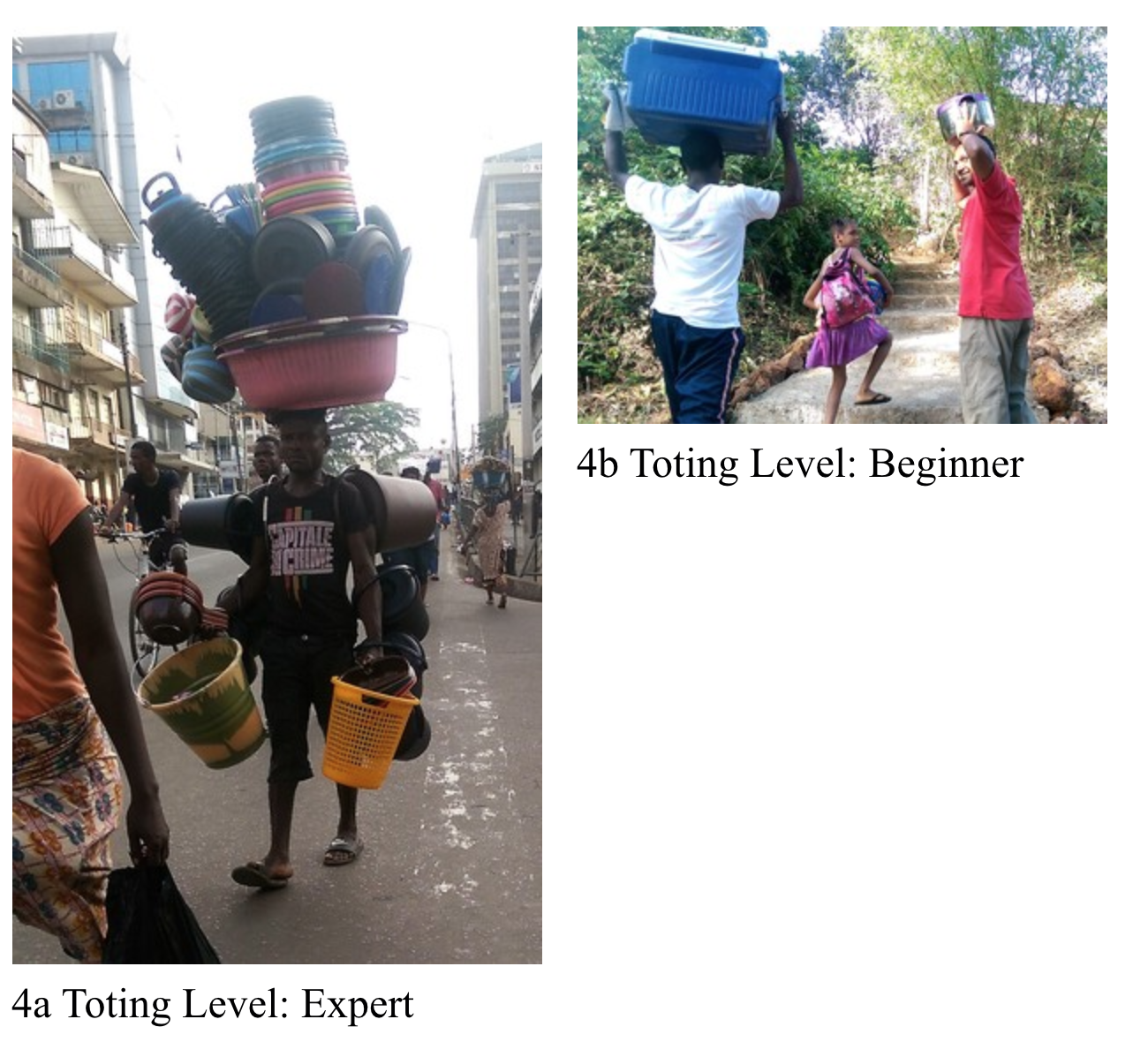

In this piece, I am honoured and excited to share Dr Raj’s circuitous journey into global health, his biggest takeaways from years in the field, and his personal tips for making your global health career a more fruitful one. Peppered throughout are some of Raj's pictures from the field and his witty commentary.

How Did Raj Find His Way Into Global Health?

Rudolph Virchow, a man described as "the principal architect of the foundations of scientific medicine," once said:

"Medical education does not exist to provide students with a way of making a living, but to ensure the health of the community. The physicians are the natural attorneys of the poor, and the social problems should largely be solved by them."

At the time when Raj was about to choose his college career, he would have agreed with Virchow. The only difference was that his motivations were grounded in his faith. "When I was 18, I decided that the most faithful way that I could follow Jesus was to be involved in medical missions—someone who does health related work among poor people."

Helping those with less became the guiding principle for many of his career decisions, including that to become a medical doctor. However, soon after earning his degree and embarking on his first few mission trips, Raj tasted medicine's bitter reality.

"When I started working as a volunteer doctor in a village in East Timor for about six months in 2007, I discovered that there were a lot of needs that I just had no ability to meet, he says. "Things like managing water and sanitation within a village, and how to do preventive healthcare."

Raj knew how to vaccinate a patient, or prescribe antibiotics to treat an infection. But he did not know how to set up a childhood immunisation programme or establish clean water supplies and enforce sanitation practices. "You realise that goodness, there's just very little impact that we doctors can make without the right systems around you," he says.

"And so that's what led me from clinical service to capacity building and health systems strengthening." He proceeded to pursue his Masters in Public Health and never looked back. Raj went from doing direct clinical work to indirectly enabling others to do clinical work.

While the map of Raj's career might look like it all panned out according to a well-written script, it was anything but. "You know," he says, "Like many things, this is probably one of those things that is going to sound a lot more coherent in hindsight than it really was going forward."

And when I asked him about the things he wished he had known earlier, Raj gazed upwards and paused. "There were lots of periods in my life where I was not sure if this is the type of work that I wanted to do. I was potentially giving up a default but lucrative career trajectory, to do something less conventional, less prestigious and less financially rewarding.”

In a society that places a premium on prestige, it takes a certain amount of courage to pursue the less glamorous thing. But Raj had long intuited that life's worth and purpose cannot be found in remuneration figures.

"This," he says, gesturing to his office in Timor-Leste, "is just the best thing I could be doing with my life right now." He wishes for his younger self to give himself fully to helping the marginalised. That would have relieved himself of the internal tug-of-war that constantly plagued him. Raj presses his lips together, his gaze thoughtful. "I would tell my younger self to just chill, and carry on. It will be totally worth it."

How Did He Know That Global Health Was A Good Fit For Him?

In paying attention to our heart's true longings and ferociously nurturing our innate talents, we can produce outcomes that would surpass even our best work in fields that are ‘trendy’ or in vogue. The sweet spot is finding a role where our internal values and our strengths and skills intersect. Discovering all of that, Raj says, "is just a function of experience and trying different things."

He saw his own career switches not only as opportunities to do good, but also opportunities to "gather some data on the things I enjoy and the things I feel I'm relatively good at."

Raj started out as a medical doctor and spent some years as a nonspecialist doctor in Singapore’s government hospitals. However, he spent significant time toggling between clinical work at home and various global health projects. Soon, the first of three factors that made him realise he was a good fit for global health emerged.

The first, was the illuminating joy he found in teaching. "I enjoyed the experience of working with somebody from one level of understanding to another." Not only did he enjoy it, he had a natural strength for it. I can attest to his use of analogies throughout our conversation.

He eventually spent close to a decade working on short-term health development and health system strengthening projects in low-resource countries. Some of these projects included empowering Timorese doctors as educators, as well as programmes to train health service providers in skills such as interpersonal communication and basic management of community health centres. Raj was also involved in developing and teaching the global health curriculum at Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health.

Next, Raj realised that he does his best work outside the clinic. "I work with ideas and data better than I do with, you know, directly with human beings.”, “I work better in systems, planning and management. In many ways, I work with humanity better than I do with real people."

And much of his work for the past few years has been exactly that. "Within an organization, either as the medical director or executive director, a lot of the work that I do is through other people,” he explains. “And so a lot of time spent is spent understanding what others are doing, and then providing direction and leadership to get the right things done."

Raj likens working in health systems management as akin to moving pieces across a chessboard. "A larger part of my work would be then finding out what my people need in order to do their jobs better,” he explains. “My job may then be to move some things in order to remove certain barriers, procure technical support or provide political cover.”

Finally, global health was the ideal setting for him to leverage his inherent skills. These are, surprisingly, the skills we often take for granted. Some of them could be as simple as the ability to type, create Excel sheets, automate workflows using scripts or create a website.

"I grew up mostly in Malaysia, Brunei and Singapore. These are high-resource settings. Anybody born and raised in such settings has almost automatically developed a lot of these skills that are very needful in global health settings." He also grew up amidst relatively efficient institutions, which he says equipped many of us with a vision of how workflows ought to be like.

"When you're in some places, you realize, good God, why on earth am I filling in 10 forms just to get a visa approval? Why am I filling in the same data in 10 different places?'” As Raj suggests, many of his invisible, culturally-ingrained skills had become more valuable in low-resource settings.

What Raj Has Learned From Years In The Field?

On medical education’s much-needed reform

"Teaching is the one profession that teaches other professions."

Good education is not just transformative. It is also life-saving. In weakened health systems that are chronically underfunded, understaffed and overworked, there is no greater imperative for education to do more with less. Raj offers two key reforms in medical education he'd like to see.

First, cut the fat from medical education. "Right now, a lot of legacy medical education systems are based on some smart people’s ideas of what the subject of medicine is about," Raj says. "Whereas what we really need is outcome-based education: we need to figure out the exact tasks a typical graduate doctor is supposed to perform, and work backwards from there."

Such reforms mandate that all curricula must prepare trainee doctors for practice. That requires shifting the current bloated focus on knowledge over to skills and attitudes, and to have students assessed as such. Raj says that while basic medical sciences such as biochemistry and molecular biology are still necessary, they are needed at a much less detailed level than is currently taught.

Second, preserve compassion at all costs. "People who enter the health professions tend to either be driven by a desire to serve and heal people, or a desire to put right something that's broken." However, somewhere along the course of one's medical education, “We take that raw material and turn it into something cynical, self-serving, and sometimes quite jaded." There might be many wrongs that call to be righted. Whether it is the profession’s cut-throat competition, sleepless work nights or otherwise. Health systems fundamental goal is to support our frontliners. Fail them and we fail our patients. Raj believes in an emerging field known as 'Healthcare and the Humanities,’ a domain that recaptures compassion and humanity with literature and poetry.

On the grounding force of purpose

Global Health has no shortage of talent, ambition, and compassion. But even among the brightest of the bunch, Raj warns that "this type of work can just be extremely discouraging." He paints a candid picture for us. "The field is often marked by a lot of failure and at times, a sense of desolation from not knowing who to go to for help,” he pauses. “ A lot of times, you're faced with problems that just cannot be solved.”

There are no words to describe the helplessness of seeing drug-resistant TB invading both the lungs of a patient-turned-friend, nor the heartache of examining a child’s sharp bones in a body ravaged by malnutrition, or the suffocating fear for mothers seeking maternal care in communities with high rates of gender-based violence and sexual assault.

Purpose, he says, helps tide him over the individual tragedies that he comes across. For Raj, his faith has become his surest defense against desolation. "If you don't figure out how to find meaning in your work, I just don't know how people will survive this kind of thing," he says, his voice steady and fingers wrung together.

Further, in an environment where pragmatism often trumps social justice, his values often war with the practical thing to do. His moral compass might say one thing, but the social, political, and cultural fabric of his working environment might force his hand towards another. But global health is also a test of grit and long-term foresight. Raj reminds himself that his work is not about him: it's about the community he is serving and ultimately aims to uplift.

On the challenges of complexity

I asked Raj if there were any secrets to strengthening health systems. His short answer was no. For all our brains and ambition, humankind has no step-by-step manual for how to help health systems go from zero to one. The problem? Health systems are just too complex.

"Singapore's health system does far better than most other places in the world. But if I take that system and try to impose it in another country that’s trying to rebuild one, there's just no way that it would fit." Trying to do that, Raj says, is like doing a heart transplant. "All health systems have got their many contingencies and paths of dependencies—from its history, its culture, to its political architecture," he says. "It is just not possible to transpose things."

People are complex. And at the community setting, they are the ones who determine which way the pendulum swings. Let us take malnutrition as an example. Early treatment in malnutrition among children is one of the most impactful interventions in global health. "When healthcare workers provide kids with immediate nutrition and medical attention, they can transform these kids' long-term outcomes,” Raj says.

Proper nutrition is gold disguised as treatment. By enabling proper brain and body development, nourishing a child is equivalent to securing a lifetime of earning capacity. The fight against malnutrition is equal parts a fight to break the poverty cycle.

But while the 'what' to do is glaringly obvious, the 'how' to do it is daunting. "How do we actually go to a community health center, go to the team that is providing that malnutrition care and help the team perform their role better? That's something that we don't know very well."

Raj and his team have tried countless tricks in the book. Educating the health teams does not seem to work, even if they retain what they learned. Material support, such as providing more accurate weighing scales, only slightly increased the centre's productivity. Monetary incentives have worked in some health centres but not others. They even tried recognising outstanding health centres to trigger a sense of pride and intrinsic motivation. While these measures have been tried and tested in different places, the results have always been mixed.

The take-home message is, "there is no silver bullet. There is no single 'package of interventions' that I can introduce to any health center and make it perform better."

On decision-making in global health

So, how does Raj decide what might work? He relies on several key frameworks. For one, "an intervention has to make sense from a first-principles point of view,” he says. "A lot of the work here is really about having some kind of educated intuition about what things work and don't work and trying as best as possible to support that with evidence." This requires asking:

- Is the evidence strong?'

- What has worked in the past and why?

- How will this intervention pan out, behaviourally and economically?'

This 'educated intuition' is not about guesswork. Almost akin to how artists can intuit the 'right' colour or brushstrokes for a painting, Raj is talking about a mental calculation of what might neatly fit into an existing blueprint. This is an intuition honed from years of tinkering melded with a deep attunement to cultural and societal needs. This often means taking an intervention from one country, making the necessary tweaks, and then testing it in a new context.

Other times, some decisions are best made because they are simply the right thing to do. Raj constantly returns to the concept of social justice and equity. "During those times, I'm just going to embrace it and say that this particular way should be done, because this is the equitable way to do it."

But if the bigger goal is to ensure that global health's moral arc continually bends towards social justice until it is completely achieved for all, decisions demand a sobering dose of pragmatism. "We sometimes come across a health policy that may be unjust because it excludes certain parts of the population. And that's simply morally wrong," he says. At times like this, he needs to remind himself that, "Those policies are what's politically feasible at this point. It's going to create the greatest good for the greatest number, so we're gonna go with it."

How Can One Begin To Thrive In Global Health?

In Global Health, the chances of burnout are high. But yet, the chances of great internal fulfillment are also high. Building on his most important takeaways, Raj offers some final tips on how to make your personal journey in Global Health more fulfilling- and enjoyable.

First, get comfortable with uncertainty.

Anyone who works in Global Health must get comfortable with uncertainty. For example, "Sometimes people just don't have email, refuse to check theirs, or simply don't own computers." When that happens, Raj says, "you actually need to go to their offices, sit down outside, and just wait for them to let you in." Sometimes, the waiting does not end with a house visit. "After you leave, you don't know the outcome until you get a call a couple of days—or weeks—later about whether or not your proposal has been accepted." Sitting through the unknown, especially when it concerns a health programme that can save thousands of lives, is an exercise that is equal parts practice and sheer will.

It is perhaps then fortunate for Raj that this uncertainty extends beyond his professional life. In Timor Leste, sweet bouts of serendipity spruce up the mundaneness of everyday life. "Without Yelp or a reliable Google Maps here in Timor," Raj says, "visiting a new restaurant can mean tasting the most awful salty noodles or the most satisfying three-course meal." Life in Timor never fails to remind him that life’s sweetest moments come from things that are least expected.

Next, learn a little bit about everything.

"In just this last one week, I had to change a showerhead, repair a motorcycle, and repair a car engine that wouldn't start." Plumbing and handy work aside, Raj also needed to create a website to host FAQs for volunteers who want to help at Maluk Timor. He even needed to do some basic JavaScript programming to automate some forms. "In Singapore, I could have depended on somebody else within the organization to do all these things,” he says. “But here, because a lot of that institutional capability is not present, I have to learn how to do them."

Raj is not talking about becoming an expert at everything. "As a rough rule of thumb, if picking up a new skill takes about 20 hours to go from knowing nothing to grasping the very basics, you should probably learn it." Quickly gaining a fundamental understanding of very many things is the key here.

A related point would be learning how to learn. Raj recalls his own experience picking up Mandarin to speak to his patients in Singapore. When he was in Sierra Leone, he had to pick up Krio, an English-based creole language spoken locally. Now, having worked in Timor Leste and finally settling there for a couple of years, he can focus on mastering Tetum. "Each time I learn a new language, I learn how to pick it up a bit more efficiently. Reaching the same level of competency for the next language I learned took a lot less time."

Finally, find joy where you work.

And when I asked Raj to share some unexpected differences between Singapore and Timor-Leste, Raj placed both his hands behind his head and grinned. According to him, the differences can't be more apparent and delightful.

"It's just the serendipitous stuff that happens all the time here." he says, shaking his head with mirth. He gives me an example, a scene that is virtually unheard of in Singapore. "You'll walk down the street and see somebody who's carrying a bunch of chickens upside down. My favorites," he says, "are the people who carry the chickens on their motorcycles." Raj tries to draw the scene with his hands. "They've got these horizontal sticks perched behind them on the pillion seat, and hanging on both sides of the stick are the chickens that they're bringing to the market." He grins cheekily, "I like to call them the biker chicks."

Conlusion: To Safeguard Health, Look Beyond The Physician

Virchow might have said that physicians should be the natural attorneys of the poor. Two decades after becoming a doctor, Raj would disagree. Safeguarding the health of any community is a possibility that can only be made real when you look beyond the physician and into the structures and institutions, both cultural and social, within which a doctor's role is embedded.

One's health represents the locus of life. It is from which all else springs: hope, joy, love, awe, spirit. While the fruits of his, as well his team’s labour may be slow to harvest, he finds no pursuit as quenching as providing others with the gift of health.

It has been my honour to be able to share Raj’s teachings with the rest of the world. If his experiences and ambition resonate with you, Global Health might just be the path for you.

Stay updated on the best insights from public health professionals.